Decoding the UCI points system and its potential improvements | ft. Raúl Banqueri

UCI points have become a crucial issue not only for teams but also for riders. They have changed racing strategies, reshaped squad compositions and captured the attention of journalists and fans.

When Movistar, Lotto, and other historic cycling teams realised the real danger looming over them in 2022, with the threat of relegation hanging over their heads, for some it was already too late.

At the time, few were following the UCI points system and team rankings closely. One of the first to do so, and the one who explained it best, was Raúl Banqueri. He understood the system better than anyone and broke it down through graphs and analysis, earning him widespread recognition.

Raúl is one of the leading experts on the UCI points system. He regularly explains it in his collaborations with Lanterne Rouge and, on top of that, he’s an old friend. I sat down with him for nearly two hours to discuss the current model, its impact on cycling development, and ways for improvement, right in the season when the three-year cycle determining World Tour promotions and relegations comes to an end.

Some organisers question the model

A few weeks ago, during O Gran Camiño in Galicia, Spain, the race director, Ezequiel Mosquera, complained about the way UCI points are distributed in races like his (2.1 category) compared to classics of the same level.

Despite expanding to 5 days of racing from the previous four and aiming for a promotion to Pro Series status, while also debating the event's calendar slot, he attributed a weaker than expected startlist partly to a system that doesn’t favour stage races.

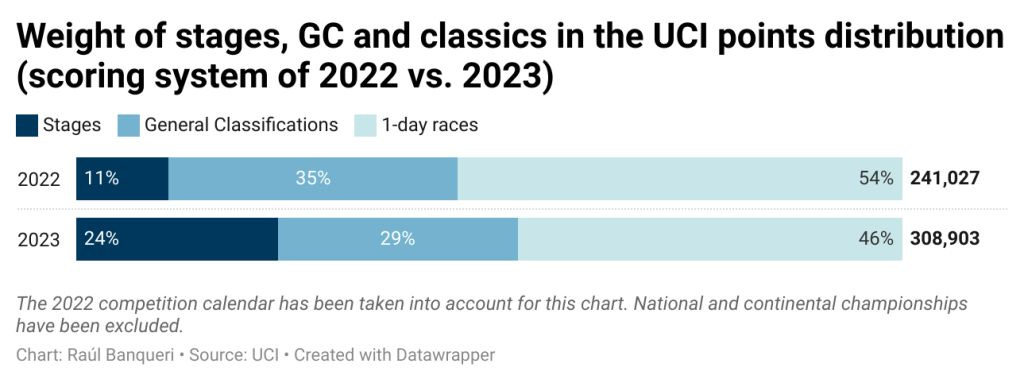

"He has a point," says Raúl. "The more stages a race has, the less profitable the points-per-day ratio becomes, and the UCI isn’t exactly encouraging the creation of longer stage races, at least in 2.1 and Pro Series events”.

“Especially problematic is the fact that in a .1 race, only the top three riders earn points, or that a stage win in a race like the Vuelta a Andalucía (.Pro), such as Diego Uriarte’s victory for Kern Pharma, awards just 20 points, the same as finishing 10th in a one-day .1 classic. The Andalucía stage win carries far more prestige and significance".

What would be a fairer system to improve the current model?

"I prefer ProCyclingStats scale over the UCI’s," says Banqueri. "There, stage wins are worth nearly 50% more points, and more riders score” (the top 8. Currently, in stage races only the top three earn points in .1 events, and the top five in Pro Series races).

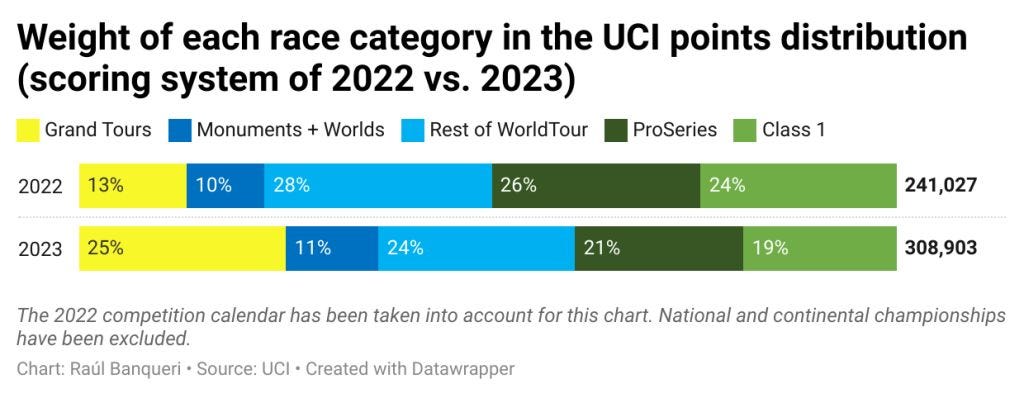

“In the UCI’s last scoring reform, they increased the number of riders earning points in Grand Tour stages from five to fifteen, and the overall share of points from Grand Tours rose from 13% to 25% of the season’s total."

So, how could a race like O Gran Camiño improve within the current system?

“In smaller races like O Gran Camiño, the race date plays a crucial role. The event is starting to overlap with other major races, such as the Opening Weekend, making it harder to attract top-tier teams. Étoile de Bessèges had a very strong lineup because teams are also looking to add racing days, despite what happened.”

If you want to distribute more points, the UCI encourages you to move up a category… but that also comes with higher costs in the form of fees. Bad weather, the overload of races, and its .1 status undoubtedly affect participation for races like O Gran Camiño. However, changing the date is not always the solution.

“In a .1 race, it’s normal to have just 3 or 4 WorldTeams, like in Coppi e Bartali or Vuelta a Asturias. Additionally, due to regulations, no more than 50% of the teams can be WorldTour. What happened in previous years, with riders like Vingegaard, was the exception rather than the rule”, says Raúl.

Another model is the Challenge Mallorca, right? (5 consecutive one-day races, under the same organisation and with the same teams participating each day, although they can field different riders and award far more points than if they were regular stage race stages.)

"In Spain, we like having a general classification, with strategy built around it. I understand Mosquera and he’s right in many of his arguments, but the model has been the same for years. And before it was even worse."

Are one-day races overvalued?

It feels like Ezequiel Mosquera’s complaint, shared by other organisers, highlights an undeniable reality. Teams prefer one-day races over stage races because they offer a better UCI points return, to the point that it has even changed the way they race, as Swiss rider Simon Pellaud told me a few weeks ago.

“Races like 4 Jours de Dunkerque (.Pro) will have one classic followed by 5 stages, instead of 6 stages. And they justify it because of the UCI points system."

Why is the UCI favouring the one-day race system?

"I don’t think they did it intentionally. They created a points system and then, along the way, made adjustments for this 3-year cycle. There’s definitely a degree of incompetence involved. The 2023 reform aimed to bring the UCI points system closer to the PCS ranking scale."

What can be improved?

This would be the year to make changes for the next three-year cycle…

"In terms of the points scale, instead of awarding points only to the top 3 or 5, it should be at least 8 or 10, encouraging longer stage races, or at least giving organisers an incentive to try it. There should also be a reward for the most combative riders, making races more competitive and exciting."

We both agree that this would be a great incentive to encourage more breakaways and competitiveness, something that has been somewhat lost with the growing importance of UCI points, but rewarding combativity would involve a subjective allocation, but perhaps it could be done through intermediate sprints or the 'golden kilometre', at points in the stage where it’s harder for sprinters’ teams to control a breakaway.

“There are fewer and fewer breakaways, especially in Grand Tours, because they’re not worth it in terms of UCI points, Raúl reflects. They offer visibility, but it has impacted the overall spectacle. This is one of the negative consequences of the points system, or rather, of how important the points system has become. It has changed the way riders race”.

“In 2023, they improved the points allocation for Grand Tours and Monuments, so that doesn’t really need to change. However, races like the Canadian classics or the Tour Down Under seem overvalued in terms of points. The UCI wants to globalise cycling, but the weight of these races doesn’t quite match their real impact”.

So, it’s like a kind of positive discrimination, I suggest.

I think there are some imbalances, I tell Raúl. Take the Volta a la Comunitat Valenciana, for example. It had a 34-kilometer TTT, the longest of the season, with a strong startlist full of World Tour teams, yet Lidl-Trek, who won, earned just 2.86 points per rider…

"Even if the riders have to split the points, maybe it should reward more. Right now, it's just too little”, tells Raúl.

And the secondary classifications? They only award points in the Grand Tours. Winning the mountain classification in the Itzulia, for example, gives you nothing. If you're up there, it means you've either been the best in the climbs or at least you’ve spent several days in breakaways. And that also rewards aggressiveness…

"Yes, it could be an improvement. It could also be attractive for sprinters in the points classification”, since some of them don’t even finish the race if the final stages are in the mountains.

The system rewards some teams, but also a certain type of rider. Someone like Alex Aranburu, a rider who is fast and climbs well in minor classics, can accumulate a lot of points.

"Yes, but until now we haven’t seen it much, since he's Spanish. Maybe this year, in a team like Cofidis. We come from a system that was worse, but the current model benefits riders like Van Gils, who excel in one-day races, but not so much endurance riders”.

“Winning both Canadian Classics gives almost the same points as winning the Tour's GC", Raúl Banqueri criticizes.

We also talked about the excessive weight of certain competitions, such as national and continental championships. Just like with the points distribution in road races, there is also a false balance in cycling’s globalization process.

"The points system in national and continental championships could be adjusted, especially considering that the European Championship is by far the most competitive. In Oceania, for example, 250 points are awarded despite having very few WorldTour riders. A team like Astana has remained competitive largely because of the points gained in Asian championships” (625 points in the 2023 Summer Asian Games, 670 points in the 2023 Asian Continental Championships, and 460 points in the 2024 CC).

"Countries with riders in the World Championships (top 60 ranking) award 100 points for their national championship, while the rest only give 50. Winning an ITT and a road race national championship in countries with very few professional riders earns 150 points”.

More than Magnus Cort winning three stages at O Gran Camiño or Van der Poel winning Le Samyn…

Points change rosters

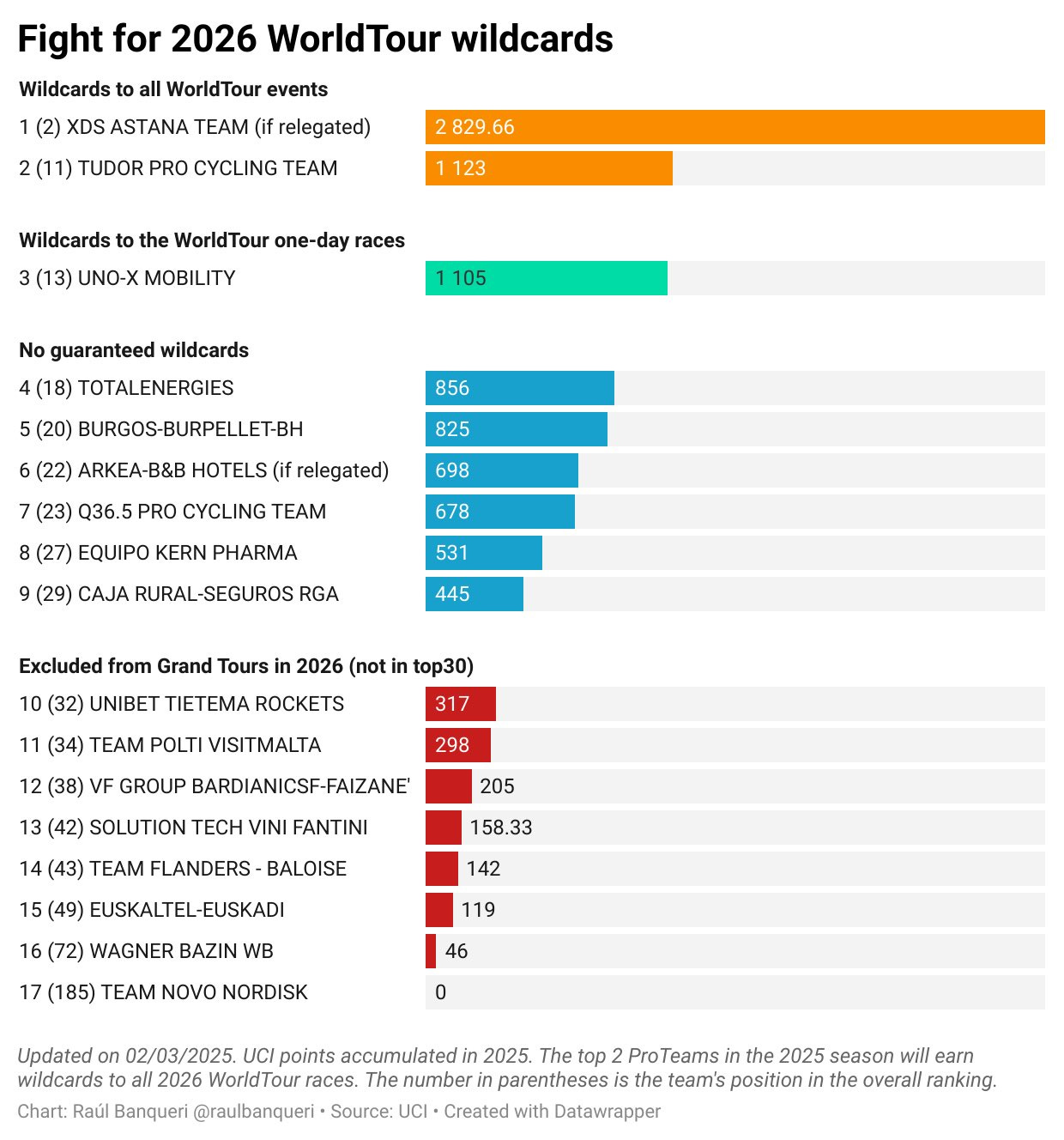

"Many teams take advantage of this situation in the hunt for ‘easy’ UCI points”, analyzes Raúl. “This is crucial for teams whose main goal is to stay in the top 30 of the team rankings, the requirement to participate in Grand Tours. Teams like Burgos BH or Caja Rural have operated this way in the market".

I share with Raúl an idea I have about how UCI points have changed team rosters. I think there are fewer domestiques, those hardworking riders who do the dirty but necessary work. Experienced guys who know how to position themselves in sprints and the peloton, protect young or lightweight riders, bring food… They aren’t very profitable in terms of points, but they are in every other way. And they are relevant in an increasingly inexperienced peloton.

“The best will survive, and strong teams will be able to have several, but mid-tier or smaller teams will minimize their presence”, he says.

“Harrison Wood is a valid example of a rider who, despite Cofidis promising him a contract renewal, ultimately had to find his way in a Portuguese continental team because of the points” (Anicolor/Tien21).

Raúl also points out that there is an inequality between teams that are under pressure to earn UCI points and those that are not, allowing them to build a more balanced team with domestiques.

Another problem is that there is much less patience with young riders, as investing in developing a young rider for 2 or 3 years is a bet that some teams can’t afford as they won’t have an immediate impact or score points.

The future and One Cycling

We talk about the projects emerging with a closed league format. Raúl tells me: “I prefer cases like Bas Tietema, who started a continental team from scratch and could eventually reach the World Tour. Or Alpecin, which began as a small CX team and grew alongside Van der Poel. Teams like Kern Pharma wouldn’t have a chance of becoming a World Tour team under that system. The idea that you can rise from nothing to the top league in the world or race in the Tour de France is important.”

What Raúl points out isn’t exclusive to cycling. We’ve already seen similar debates in football, with the currently failed Super League project, or in basketball, with the EuroLeague, even though each sport and model has its own specifics.

The relationship between sporting merit and closed leagues is complex and often frustrates fans. However, we must remember that, in practice, the current World Tour model, a descendant of the ProTour introduced in 2005, is already a semi-closed system, where the same teams compete against each other in nearly all major races. Tudor, for example, has gained WT status this season, securing invitations to all major races while awaiting the outcome of Grand Tour wildcards, where they are expected to feature, at the very least, in the Tour de France.

The key issue is the distribution of TV rights. And if there is revenue sharing, there must be a clear definition of who gets a slice of the cake.

Points, invitations, and Grand Tours

There is a lot of debate surrounding Grand Tour invitations.

Two years ago, the UCI introduced a team ranking system that limited potential wildcard invitations to the top 50 teams in 2024 and the top 40 in 2025 for the Giro, Tour, or Vuelta. In 2026, this threshold will rise to the top 30, significantly restricting which teams can participate in a Grand Tour.

The goal? To increase opportunities for strong second-division teams, even if they don’t share the same nationality as the race organiser. As a result, teams like Tudor (Switzerland), Uno-X (Norway), and Q36.5 (Switzerland) are likely to gain access to the biggest races on the calendar without yet proving their sporting merit.

This is what Javier Guillén, La Vuelta’s director, was referring to recently when he stated that he didn’t want to feel responsible for the survival of any particular project. His comments were directed to the four Spanish ProTeams, Caja Rural, Burgos BH, Kern Pharma, and Euskaltel, all of them looking for a spot in La Vuelta a España. He emphasised that race organisers reserve the right to invite the teams they believe will provide the best spectacle.

Raúl Banqueri, however, sees Guillén’s stance as somewhat “unrealistic”. For these teams, “La Vuelta is everything”. “In terms of sponsorship, the exposure they gain from participating in Spain’s biggest race far outweighs any other event, particularly when it comes to casual cycling fans. Their very survival depends on getting a Vuelta invitation”

Perhaps an additional wildcard could help. In this regard, the Giro has an easier situation, as Lotto has already declined its invitation, and Team Solution Tech - Vini Fantini is out of the top 40 in the team’s ranking.

There is a communication problem

The UCI has a ranking, but it does not promote it properly.

“If the UCI has a system that has generated so much interest, partly thanks to Twitter users like me, they should build a storytelling around it through graphics, stories, and context. Additionally, the scoring system is too complex for the average fan to understand”, Raúl explains.

“It could be promoted better. It is now generating more interest in smaller races that previously didn’t attract as much attention”.

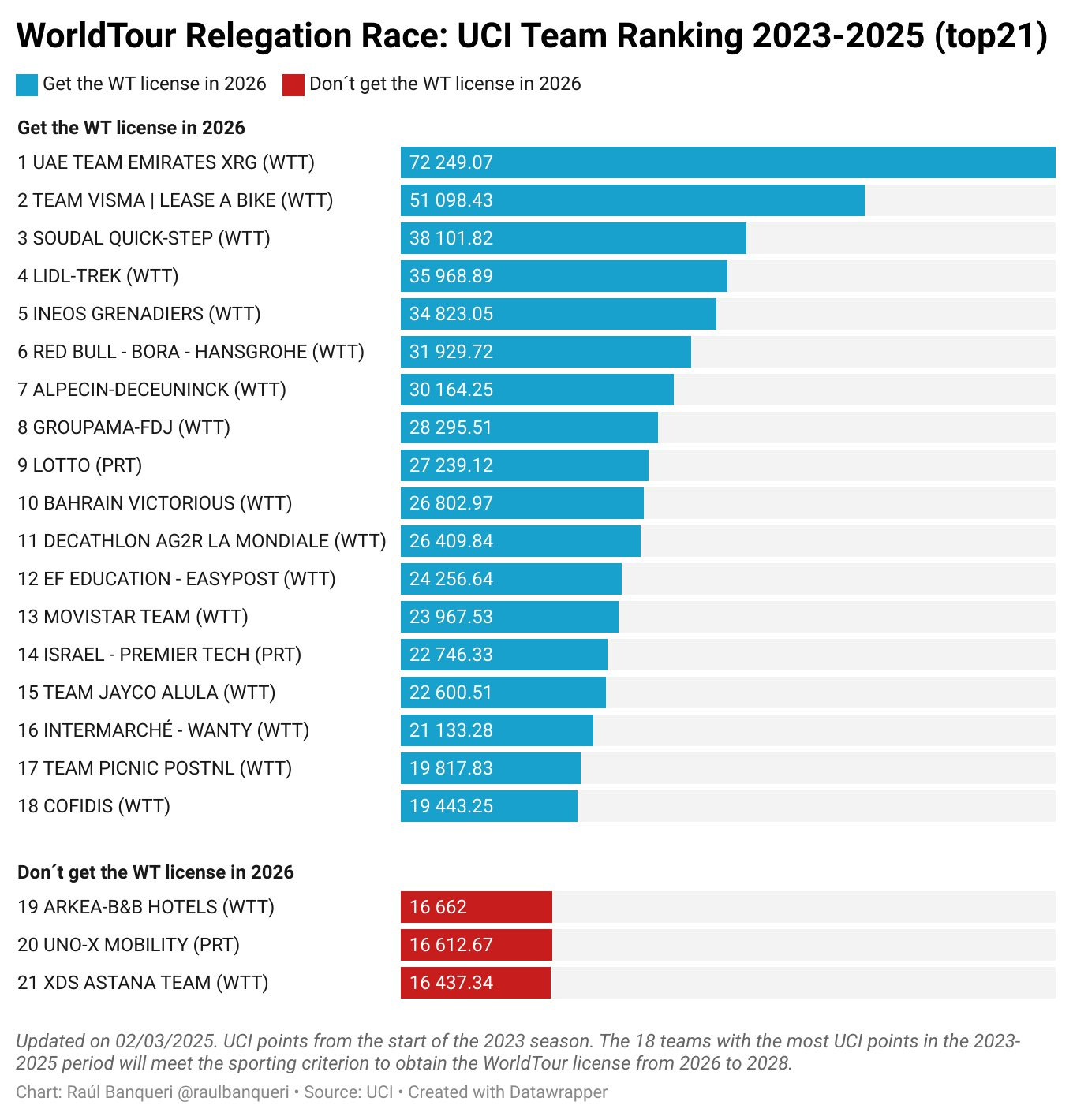

The triennium ends and someone has to be relegated

Astana’s level in 2025... They are playing their cards, but there are many races where they haven't raced to win because it's more beneficial for them to have 3 riders in the top 10 rather than fighting for victory. To me, this seems like a distortion of the system, I tell Raúl. Perhaps an even greater points gap between first and second place would help for these cases.

“That could be a solution”, says Banqueri, “having the second-place finisher earn half the points of the winner. However, since the gap between first and second is sometimes minimal, it could be unfair for the runner-up to receive significantly fewer points than the winner”. [Under the current system, in races .1 the winner gets 125 points, the second 85, and the third 70].

“I understand why Astana plays that way. A race strategy can involve sending riders ahead to later sprint with their strongest men. It’s a tactical variation that allows them to be aggressive while also considering UCI points. People tend to blame everything on the points system, but that’s not entirely true”.

Before this season, Astana seemed a relegated team, but their performance jump has been huge. “Take Scaroni’s case, for example. They’ve closed a gap of nearly 2,000 points, and now avoiding relegation is possible”.

“Right now, we’re entering a tougher part of the calendar for Astana, so it’s likely they won’t keep up their scoring pace. But it also depends a lot on the Grand Tours. Even Uno-X, which had a great run last year, couldn’t maintain the same rhythm towards the end of the season”.

Being in the Grand Tours might end up being the key factor.

“Yes, the Giro and Vuelta offer more opportunities to score because of the high level of the Tour, especially if we get editions where breakaways succeed often. In the Tour, UCI points are much harder to get, though they do provide great visibility for sponsors”, Raúl states.

“Sometimes we lose focus”, Raúl tells me. “Some teams are skipping big races to chase points elsewhere… just to secure a future spot in the World Tour and be able to ride the big races, like Lotto. It’s a bit contradictory”.

Who could be in trouble if Astana keeps going this way?

“I don’t think Intermarché will struggle. They have a big gap and should score heavily in the Spring Classics”.

Yes, though they are the most dependent on a single rider. If something happens to Girmay…

“Last year, Girmay scored 3.350 points, an insane amount. Without those, they’d be on the verge of relegation, but I don’t think they’ll suffer. Picnic could be more at risk because they’ve shown they aren’t too concerned about UCI points, focusing instead on big goals. Among the bottom teams, they are one of the ones that races the least. If they deliver in the Grand Tours, they’ll be fine, but if things go wrong, they’re playing with fire”.

“It’s a risky bet, but I get it. If they find themselves in danger after the Giro, I expect them to adjust their calendar for the rest of the season. It’s a risky approach, but it shows confidence in their young talent. Cofidis, on the other hand, lacks the depth of Picnic to focus only on big races. Movistar already adapted its calendar in 2022 when they were close to relegation, entering many extra races”.

You became well known in Spain and the cycling world for closely tracking Movistar’s near-relegation crisis in 2022. How do you see them now? They seem to be focusing on long-term contracts for young riders, similar to UAE’s model, but with a different profile of talent.

“They’ve had great news with the Telefónica sponsorship renewal, which gives them financial stability and allows them to secure riders like Romeo and Javier Romo. Their problem was that fans were used to seeing them fight for Grand Tours, and that’s no longer the case”.

“The audience has started to understand that Movistar must now be judged by a different standard as they can’t compete financially with UAE, Visma, INEOS, Lidl, or Red Bull. They’ve educated the public in that sense, and winning a stage in the Giro is now highly valuable. They are building a strong identity around young Spanish talent”.

“They invested in a Classics squad with Iván García Cortina as a leader, but that bet didn’t work out. To build a solid Classics team, they should have raced more small classics, like Le Samyn”.

Image matters, I tell Raúl. In modern cycling, besides UCI points, the Classics are gaining much more attention in Spain. Movistar can’t ignore these races. Now they have Iván Romeo, though he has said he doesn’t want to specialize in Classics yet…

“I think it would be a mistake, without knowing his exact physical data, to focus only on GCs. I’m glad he renewed with Movistar because he would have been an ideal domestique for UAE, Visma or a team like that, but at Movistar he’ll have much more freedom”.

“He’s a smart racer, as he showed in the Volta a la Comunitat Valenciana, with great tactical awareness and strong bike-handling skills”, Raúl says about Romeo. “And the fact that he’s not yet a big name could actually work in his favor in the Classics, as he’ll be given more tactical freedom”.

Very interesting! I wonder what the effects of the points system will be on lower-level teams if there is no change in the system