Safety at the heart of the debate on cycling’s future

The Challenge Mallorca and Étoile de Bessèges safety issues expose a growing battle between riders, teams, the CPA and race organisers.

Safety has become the biggest talking point at the start of the season. Yes, even more than the races themselves, the uncertainty surrounding the 2025 Rwanda World Championships, or how many UCI points Astana might collect in their desperate bid to avoid what seems like an inevitable relegation.

Unilateral Decision at the Challenge de Mallorca

The first major incident occurred at the Challenge Mallorca, a series of five one-day races on the Balearic island. On the 1st of February, the Trofeo Andratx - Pollença, the fourth race in the series, was supposed to take place. However, just over 20 kilometres into the race, the riders came to a standstill.

The reason? Dangerous road conditions on the opening loop before the race hit the main road towards Puig Major, the key climb of the day. According to the riders, there were multiple crashes—dozens, as confirmed by teams and representatives from the CPA, the riders' union.

What was most striking about this case wasn’t the cancellation itself but how the decision was made.

Faced with unsafe conditions and repeated crashes, the riders stopped racing. After discussions between the 3 rider representatives at the event, they unilaterally called off the race. There was no negotiation with the organisers, nor any attempt to neutralise the dangerous section before continuing under safer conditions.

Having spoken with riders, teams, organisers, and other staff present in the race convoy, one thing is clear. “The road was like an ice rink,” said a member of the race organisation who was following the day’s early breakaway, which already included several ProTeams and Continental squads.

“When we heard that UAE and Tudor had stopped behind, we knew the race was dead.”

On the A la Cola del Pelotón podcast we talked with the race organiser Manuel Hernández and Jonathan Lastra (Cofidis), who shared their insights on the controversial decision to halt the race.

Hernández downplayed the crashes, stating that riders had been warned via race radio about dangerous sections. However, Lastra countered that once a race is underway, it’s nearly impossible to control a high-speed peloton driven by multiple interests.

Hernández and the CPA

Hernández also revealed that CPA president Adam Hansen had contacted them that morning not about the route’s safety, but regarding poor tunnel visibility, an issue the organisers promptly resolved.

This contradicts claims that CPA had flagged serious dangers on the course.

Adding fuel to the fire, Hernández had a verbal clash with Movistar DS José Joaquín Rojas, who justified the riders’ unilateral decision by pointing out the absence of organisers on the race. Hernández retaliated, calling Rojas “shameless and a liar.”

Lack of communication and a divided peloton

According to Lastra, confusion reigned in the bunch:

“97% of the riders had no idea what was happening. Most of us thought the race would resume.”

He felt powerless in the decision-making process and suggested that better communication could have prevented the cancelation. He also hinted at growing frustrations from previous days, suggesting that removing the initial loop, the most dangerous section, might have avoided the crisis.

The controversy raises some questions:

How could a WorldTour team like Cofidis remain unaware of such a major decision?

Why weren’t race commissaires consulted before cancelling the event?

Could the organisers have acted faster to find a solution?

What about the refs?

Cycling might be the only sport in the world where the referee, in this case, the UCI-appointed chief commissaire, has no real authority over whether a race continues or gets cancelled.

This isn’t just an isolated incident. We’ve seen it time and time again, even in Grand Tours. Take the 2023 Giro d’Italia, where the Crans Montana stage was cut to just 70km, removing the Col du Grand Saint-Bernard. The weather conditions did not demand such a drastic change, yet the stage was shortened, setting a dangerous precedent. The double-edged sword:

Riders risk being seen as weak by fans, pressured into future protests.

Organisers may pre-emptively weaken routes to avoid controversy, altering their races identity.

In fact, Mauro Vegni and his team seem determined to prevent future cancellations, designing a toned-down 2025 Giro with fewer high-altitude climbs, a departure from the race’s legendary high mountain battles.

Jonathan Lastra shared a revealing insight about Crans Montana:

“We shortened the stage when we shouldn’t have. The next day, I was freezing, almost 0°C, but after what had happened, no one dared to speak up.”

Second act: lack of control at the Étoile de Bessèges

The Étoile de Bessèges has long been a staple of early-season racing, offering a mix of forests and scenic rural landscapes. But this 2025 edition has been pretty different.

🔴 A car driving against the peloton on the second stage caused a massive crash, forcing Maxim Van Gils, one of Red Bull Bora-Hansgrohe’s key signings, to abandon. Everyone is equal, but some are more equal than others, and when such an important rider is involved, the spotlight shines even brighter.

🔴 The very next day? Another car appeared in the middle of the race, this time at a roundabout. The riders had had enough.

The response:

Soudal-Quick Step, INEOS, Lidl-Trek, AG2R, EF, Uno-X… Several top teams quit the race.

Organizers offered a new route, but the damage was done and many refused to continue.

The race completed its 4 stages, but its credibility took a major hit. Others stayed, but the race was already under fire and even though it continued, its future is now uncertain.

Each race organizer (and each country) has its own rules and conditions under which they build their event. In the case of Étoile de Bessèges and the unacceptable incidents that occurred, two key factors come into play:

The high cost of security in France.

A common issue in cycling: riders compete in the race and often don’t think about the motorcycles, whether from the police or race officials, that need to pass through the peloton to secure dangerous sections or block intersections.

Many cyclists refuse to let them through, fearing they’ll lose their position in the peloton. Benjamin Thomas (Cofidis), one of the riders’ representatives, admitted this happened in the Étoile.

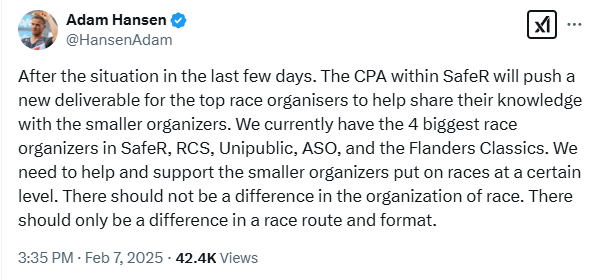

But trust me, it also in the Tour de France, despite CPA president Adam Hansen blaming it on the inexperience of smaller race organizers.

The reality of cycling is much more complex. What happened in Bessèges is inexcusable, but it’s not due to a lack of know-how, nor do these organizers need Prudhomme, Guillén, or Van Den Spiegel to lecture them. Let’s be clear about 2 things:

Big race organizers already support smaller races that are essential to the calendar.

If we sat major and minor organizers in the same room, we might be surprised by who actually knows more about how to ensure race safety with limited resources.

Accidents in Lombardia, Roubaix or even Le Tour:

The future of Bessèges

The race organizers have admitted mistakes, but they seem resigned to their fate. Claudine Fangille, president of Étoile de Bessèges and daughter of the race’s former organizer, said:

“We, with the Étoile, don’t gain anything. We are here to make the riders race. If we are not here next year, personally, it doesn’t matter, I will have fewer worries.”

Meanwhile, Romain Le Rou, head of race security, admitted:

“A much deeper effort will be needed—not just for the Étoile, but for cycling as a whole.”

They face an uphill battle. The race’s reputation is damaged, and after the UCI’s weak statement, they now threaten heavy financial penalties that could put an end to the race.

Some teams that stayed in the race have been criticized for prioritizing UCI points over rider safety. But in this chaotic conflict, with no consensus, communication, or effective intervention—just like in Mallorca—some riders have stood by the race. Arnaud De Lie said he stayed out of respect for the organizers, adding:

“Without races, we’d have to find real jobs.”

Other events, like the Mont Ventoux Classic, have also shown solidarity with the Étoile amid this situation.

What’s next?

Søren Wærenskjold, the Norwegian cyclist who refused to race in the AlUla Tour due to moral concerns about the event and the regime behind it, has proposed the introduction of circuits in cycling. Many teams and key figures have echoed this idea. After talking to Lotto, they suggested:

“The use of closed circuits with more localized loops. This would allow riders to become more familiar with the course lap after lap, increasing overall safety.”

Similarly, Jean-René Bernaudeau (TotalEnergies) said:

“Some models need to change. Maybe we should please the fans and create circuits that pass the same spot five times.”

But zero risk doesn’t exist—not even with circuits in the middle of the desert. Preben Van Hecke (Alpecin) reminds us: “Cycling is a dangerous sport.”

Ironically, what caused the crashes in Mallorca was a loop similar to a circuit. Reducing races to just a few kilometers doesn’t eliminate danger—it shifts or concentrates it, depending on fate. But whether we like it or not, this is where cycling is heading.

Organizers can profit from VIP zones, cut logistical costs, and reduce unpredictable factors, but circuits also limit course diversity and restrict the places races can go.

At the end of the road: One Cycling

Richard Plugge, one of the masterminds behind One Cycling, wants to reshape professional cycling. How? And more importantly, at what cost? We still don’t know. He promises financial stability for teams in a sport with no TV rights revenue and no closed league—although, in reality, WorldTeams already function as one.

With so many teams, race categories, and organizers, cycling’s solution has been as "innovative" as in football, tennis, or golf: Saudi money.

But key questions remain:

How will they create a parallel circuit to UCI and ASO?

Where will these races be held?

Will they be anything more than glorified criteriums?

And most importantly, who will pay to watch a sport in the street that has always been free, rolling past people’s homes for nearly 140 years?

Safety will return in 2025. No doubt.

Cyclist safety, whether in a literal sense or in extreme weather protocols, will be a major topic again this season. That’s a certainty. And it’s a good thing that it’s finally being addressed, that riders are standing up for themselves instead of being herded like sheep through dangerous conditions.

But they shouldn’t forget one thing: these smaller races are what keep the sport alive. They provide race days, give meaning to their careers, and sustain the ecosystem of cycling.

Without race organizers, there are no races. And without spectators, there is no cycling.

A crisis of communication

This issue isn’t black and white.

Communication is outdated for the 21st century.

Small race organizers are financially on the brink.

The UCI is a bureaucratic giant, but not a judge in real life race situations.

The CPA reacts too impulsively, often with Twitter outbursts rather than structured dialogue.

The relationship between riders and organizers is breaking apart. If these smaller races disappear, an entire category of cyclists and teams will be left in the dark.

And yes, let’s be clear: pro races cannot function with cars interfering with riders on the road. That’s unacceptable. But the way Bessèges has been abandoned feels telling: it’s small, seen by some as little more than a “training race with a bib”, and by others as nothing more than UCI points to grab.

The bigger picture: cycling at a crossroads

These incidents—whether in Mallorca or Bessèges—are just the surface of a much bigger battle: the fight between tradition, business, and the industry of cycling. And something tells me… we won’t have to wait long for the next chapter.